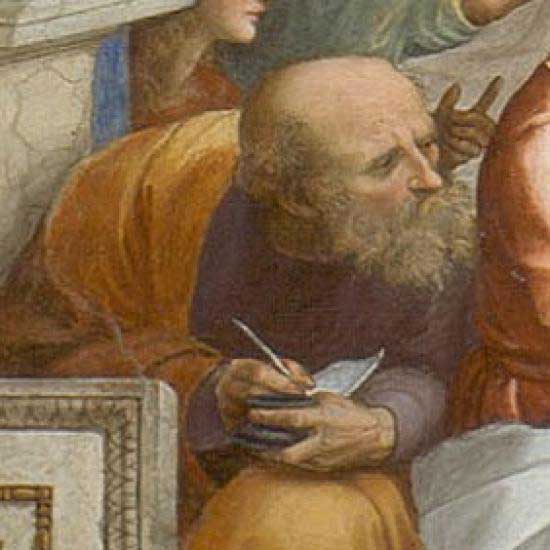

One of the special educational services NameStormers offers is access to the sage naming philosophies of the revered Naru (Naming Guru). (The identity of the Naru is protected so he/she can go about day-to-day life without being chased down the street by marketers and branding strategists demanding one-on-one audiences.)

1) Think like a customer, not like a product developer. (Would you have ever named a computer “Apple,” a shoe “Nike,” or a coffee “Starbucks”?)

Customers need to connect with a name, often on an emotional level, in order to connect with a brand. There are no “how to’s” for forcing customers to identify with a name, just like there is no formula to find people you like and who will like you in return – it’s just a mutual “feeling.” Customer-centrism is often better described as a team ideology to really get inside customers’ shoes. Asking questions like, what do I (the customer) really need? What would make my life easier? What problem can this product solve that I don’t even realize I face? While this may sound more intangible than actionable, Corporate Culture and Performance credits customer-centric organizations with a 36% higher ROI (return on investment) than their industries’ mean performance. As for naming strategy, start with how you would describe your target market. If they’re a younger, funkier group, focus on names that resonate with that demographic.

2) Memorability, not likability, is what it is all about.

If, when testing a group of names, one name consistently ranks as “liked most” many people would consider that a strong, favorable indicator. Likability is NOT the end all be all. What good is a name that is well-liked if no one can remember it? Presently, in the day of Facebook and other powerful social networking tools, if you forget the name of that one person you really wanted to follow-up with, chances are you can remember enough about them to find their contact information on Facebook without too much trouble. Products and services do not always have the luxury of context clues. Memorability is the one measure that always counts with customers. If they can’t remember the name of a product, the chances of them effectively telling others about it, much less coming back to get it for themselves, is slim to none.

3) Passion from a few is more important than consensus from all.

We all have experience with customer reviews – the people who post them either seem to love the products/services they review or hate them. Just like in life, not every person who sees your name is going to love it. That’s okay. As a matter of fact, it’s better that way. Chances are, you’re polarizing those who fall nowhere inside your consumer segment. As long as the name resonates with that segment, and leads to people who post at least once a day about how much they love everything about that product and name, then the name is doing exactly what it was designed to do – attract customers.

4) Controversial names are better than safe names.

This really ties back to memorability. Names that turn heads, drop jaws, make statements, and/or lead to scathing commentary on that one obscure blog that hasn’t praised anything in 10 years, are okay. Controversial names make waves, create buzz, and do a lot of work for you with little to no support from marketing dollars. While these sorts-of names do have inherent advantages, we don’t necessarily advocate creating a name that is divisive just for the sake of creating contention. Controversy doesn’t have to be the focus, but it also doesn’t have to be a reason to drop a name either.

5) Emotional names are better than literal / descriptive names when developing a new brand. The reverse is true when developing specific product names underneath a family brand.

Think about politicians. As much as they rely on area-experts, and call academicians to share their quantitative research so they can know, unemotionally, through numbers exactly what they should and should not vote for, that is rarely what they use to decide how to vote. Talking to many academicians at one of the top-tier research universities in the United States, they recount that politicians think they want empirical research to tell them what to do and how to craft policy, but time and time again, they vote and create this policy based on pure emotion. Doctorates from vastly different disciplines recount how much more effective a personal story filled with emotion and angst was at swaying politicians’ votes than the most compelling research they had seen presented. Naming for a new brand is largely the same. It’s much easier to connect with customers through their heart strings than through their cerebellum – emotionally evocative names are typically much more effective for new brands.

The Naru is off to meditate, reflect, and gain additional insight. Stay tuned for the Naru’s next installment.